|

By: Paul S Cilwa |

Occurred: 5/17/2007 |

|

Page Views: 1,705 |

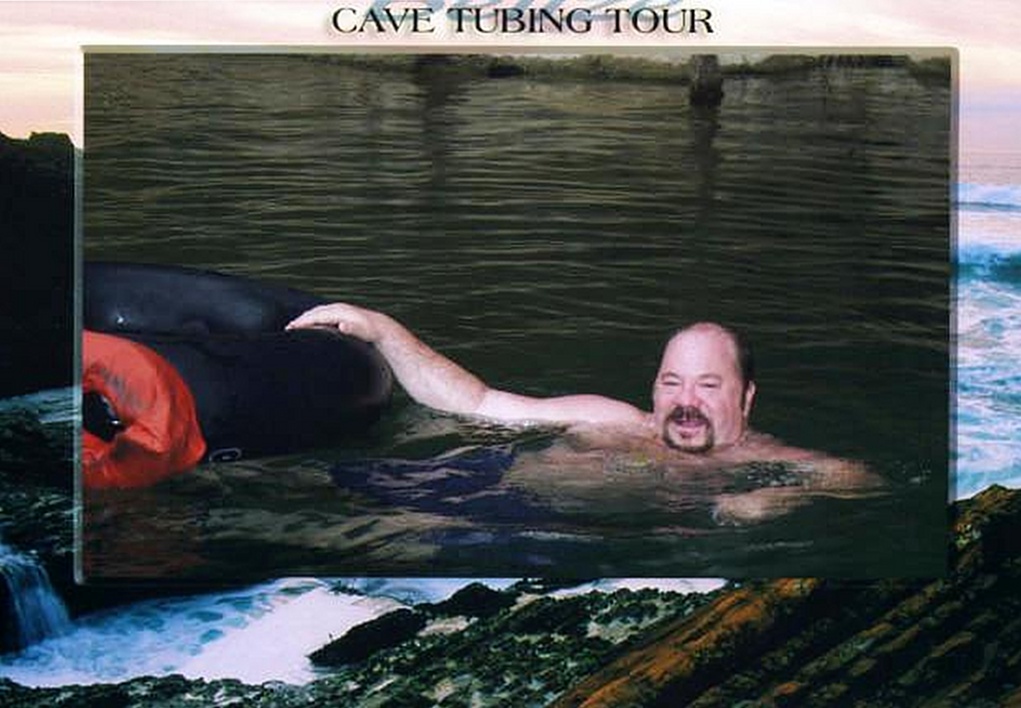

| I go cave-tubing and while the rest of the family goes ruins-touring in Belize. |

Some time before we awoke, the ship anchored offshore at Belize.

A wide, shallow beach requires ships to anchor far offshore in deep water;

getting to shore required a 45-minute tender ride. (The ride to Grand Cayman was

only ten minutes.) Michael, Mary, Karen and Zach were going on an excursion to

Xunantunich, a Mayan temple

complex. I was going on the Cave Tubing excursion.

And Dottie, Frank, Cailey, Joe and Kathy slept in,

planning to just go into town and shop. But those of us with excursions had to

meet in the Follies Lounge at 8 AM, where we were herded onto tenders and taken

to shore together, ahead of those with no fixed schedule.

When I boarded my bus, I immediately heard my name: "It's Paul!" a woman's

voice said, pleased. I turned to see a young, attractive couple sitting in the

front seat and smiling at me. "We heard you sing last night," the man said. "You

were wonderful!" his bride added. They introduced themselves as Jason and

Angela—all while the people behind me waited to sit down—and I managed to slip

into a seat one row behind them. They were from Cincinnati and Indianapolis,

respectively; but now both lived and worked in Sweden. As with me, this was

their first cruise, and their first time in Belize.

As mentioned previously, I had bought an underwater digital camera to take on

this excursion, which turned out not to actually work. It's a pity, because the

trip to the caves was quite scenic and most educational. Belizean tour guides

must be well-trained and probably by the same source, because the spiel received

by Mary, Michael, Karen and Zach as they rode their bus to Xunantunich was, I

later found out, virtually identical to the one I heard.

An item that impressed us all was the explanation that school kids wear

different uniforms, each unique to its school. If a school kid is found

wandering the streets, he or she is picked up by the police and returned to

their proper school, where they are "whipped". I don't think the guide actually

meant whipped with a whip, but definitely struck; because he explained

that "corporal punishment is legal in Belize." At this, a sizable portion of

each bus applauded. "It doesn't end there," the guide continued. "When

the child gets home, he has a note from the teacher explaining that he was

punished that day and why, and is beaten again by his father. And then, next

weekend when the grandparents come to visit, they are told and he is beaten

again."

On my bus, Angela asked the question, "With all this corporal punishment of

the young, what is the crime rate?" The guide assured us that, while Belize has

crime like any other country, the rate is quite low. However, when I

checked this figure, I found that Interpol puts the reported crime rate in

Belize at 10 reports per 100 population per year, twice the rate of the U.S.

What's more, according to

Transnational Issues,

Belize is a source, transit, and destination country for men,

women, and children trafficked for the purposes of labor and sexual

exploitation; women and girls are trafficked mainly from Central America, and

exploited in prostitution; children are trafficked to Belize for labor

exploitation; Belize's largely unmonitored borders with Guatemala, Honduras,

and Mexico facilitate the movement of illegal migrants who are vulnerable to

traffickers; girls are trafficked within the country for sexual exploitation,

sometimes with the consent and complicity of their close relatives; there are

unconfirmed reports that Indian and Chinese migrants are trafficked for

involuntary servitude in homes and shops.

This is what happens when children who are beaten grow

up. Not having been respected as children, when grown they don't

respect children themselves. What goes around, comes around. Applaud

that, bus riders!

We drove through a residential section in which the homes looked to me

something like a 1960s neighborhood in South Florida—cement block homes,

single-storey, generally three-bedrooms. We were told this was where the

wealthier people lived. The home of a doctor was pointed out, and that of the

Prime Minister, neither of which was substantially nicer than the others. All of

them would be considered lower middle class at home.

We then passed through a

section of ancient frame dwellings with sagging clapboards and

peeling paint. "This is one of the neighborhoods of our poorer

citizens," the guide stated the obvious. "But our poorest Belizeans

are very happy." No one applauded or commented. I will

point out that there wasn't much graffiti, and the area didn't

feel crime-ridden. Nor did the faces of the people look haunted

or gaunt. But I didn't exactly see jolly either.

Soon, we passed beyond the outskirts of Belize City and into the rainforest.

The road was paved and in good condition. We passed stretches of mangroves,

which our well-informed guide explained processed water coming down from the

hills, allowing only clean water to trickle into the Caribbean, which was why

the coastal waters here were so clear. He explained that, in years past, this

process wasn't understood and the mangrove swamps were cleared until it

seriously degraded the clarity of the coastal seas as well as the quality of

Belize City's drinking water. But that was decades ago, and since then mangroves

have been replanted and people no longer try to clear stands of them.

We passed steep mountains where Mayan people still live and preserve their

culture and ancient religion except, the guide assured us, they no longer

indulge in human sacrifices.

"Are you sure?" one of the passengers asked, jokingly (I think).

"Pretty much," the guide deadpanned. "But you don't have to worry—we sent

another busload of tourists into the forest ahead of you."

We then made a left turn onto a dirt road and passed a village of tin shacks,

the occasional wooden house (made of un-planed tree trunks tied together) and

exactly one cement block building with a thatched roof and no doors or window

glass. Clusters of residents and many sparsely-dressed children smiled and waved

at the bus, and the passengers waved back. I noticed, as we drove past, that

each dwelling, poor as it looked, contained a TV set.

A few miles down the road we turned again onto an even less promising

dirt road. The bus had to slow down to accommodate the ruts and washed-out

places. This road did not run straight; it wound and curved, sometimes around

low hills, sometimes apparently on a whim. At one point we came upon a beautiful

home, something anyone would love to live in, surrounded by exuberantly blooming

flowering bushes and trees and tasteful "No Trespassing" signs. The guide

explained that this house had been purchased by an American twenty or so years

ago. It had no electricity and no phone, but he and his wife lived there and

liked it. I could only imagine how this erstwhile hermit felt about the

dozen tour buses that now daily passed his remote home on the way to the caves.

The cave tubing company had a compound that included a place to eat, showers

and bathrooms, lockers and a small, open-air gift shop. I got a locker and put

my towel into it, along with my shirt and cap—I couldn't see needing them to

protect me from the sun when I would be in a cave. We then were handed an

inflated inner tube and a head-mounted flashlight, and led into the rain forest.

"Are there any monkeys here?" one of the female passengers asked as we

walked along the wide and well-maintained trail.

"We have one species of

primate in the forest, in addition to ourselves," the guide

acknowledged. "There is a troop of howler monkeys that sometimes

comes along this way."

"Will we be able to see them?"

"If they come this way. But most likely, if they do what you'll notice is a

light rain coming down on you…only on you, and only directly beneath the

monkeys."

Everyone made an "eew!" sound.

"But if you don't react

sufficiently to being pee'd on," the guide continued, "next they'll

start throwing poop on you."

"Wow!" exclaimed another passenger, a New Yorker with a biting sense of

humor. "We sure can't get poop thrown on us at home for

this kind of money!"

The guide pointed out a mahogany tree, and commented on the healing and

anti-fungal qualities of its bark, which is often overlooked in enthusiasm for

the tree's hard wood. "The rain forest is nature's pharmacy," he repeated

several times. Nevertheless, he was adamant that we not touch any leaves or

trees, or let them touch us, lest we suffer a severe allergic reaction. The

trail was so wide, that this wasn't much of a problem.

After about three quarters of an hour, we came to the opening of the caves.

All along the way, the rocky landscape was chalky white and sharply and

intricately carved into bizarre, nightmarish shapes. The cave opening was just a

large hole among a thousand smaller holes. But the river flowed right into it.

"There are two rapids in this river," the guide warned us. "They are very

shallow; so when I yell, 'Butts up!' no one should ask me, 'What?' I am not

saying 'What's up?' I am warning you to get your butts up. Does everyone

understand me?" We assured him we did, and got into our inner tubes and allowed

the river current to take us. Which it did…slowly.

"You may have noticed that the current in this river is very slow," the guide

said. "This is our dry season, and last year's rainy season didn't have a lot of

rain, so the river runs much slower than normal. So you will need to do some

work. If you don't paddle, you will not get out of the caves in time to go

home."

Some people were paddling already, having noticed that we were simply not

moving otherwise.

But first we hit the "rapids" (obviously not the American use of the word)

where "butts up" wasn't adequate for the likes of me who comes complete with a

very substantial butt. When I lifted my butt, my weight pushed the rest of the

inner tube firmly against the pebbles lining the stream and it wasn't going

anywhere. I had to get out of the tube and walk it to where the

stream deepened and I could, again, float.

The light from the large opening made things visible quite some distance into

the cave. The water was cool but not cold, and the air moist enough that it

didn't chill the parts of our bodies exposed to it. Of course, there was one guy

who was a real body builder with a fantastic physique but no body fat and

therefore no natural insulation. He started shivering early on while his

girlfriend humiliated him by remarking out loud how he really needed to eat more

so he wouldn't get so cold and

shiver like a little boy. But, other than such expressions of deep and

abiding love, the cave was fairly quiet as most of us were captivated by the

stalactites and columns (not many visible stalagmites), all purest white, like

drifting through a ghost's castle.

There were a large number of circular holes in the ceiling, which I noticed

when Jason pointed them out to me. I was puzzled as to what they were for a

moment, then realized: "Those are from stalactites that have fallen," I

explained. "Their shattered remains must litter the river bed along here." I

wondered if some earlier, unruly tourists had pushed against the stalactites,

breaking them. I hoped not; but I had never seen a cave where such a large

portion of stalactites had fallen. And I found it odd that the holes

were to be found only above the middle of the river, where rafts would drift.

We came upon a side opening to the cave, through which daylight filtered

through a heavy growth of plants. Other than that, it was pitch black until we

reached the endpoint, the place where the river exited the cave system. Our

visit had been very pleasant and enervating, not fantastic or awe-inspiring but

satisfying nonetheless.

When we returned to the compound and had put away our inner tubes

and turned in our headlamps, we were served a delicious, "typical

Belizean" dish of rice and beans cooked in coconut milk, coarsely

mashed potatoes, and baked chicken. It was very good, if blander

than I had expected—I couldn't really taste the coconut.

I sat near Jason and Angela so overheard when Angela complained to her

husband about her earache. "It's killing me," she confessed. "I wish we knew

where we could get some kind of ear drops."

"I brought swimmer's ear solution with me," I interjected. "Just in case, but

none of my party seems to need it. I'll be happy to give it to you when we get

back to the ship."

"I'll buy it from you," Angela offered. "That's just what I

need, I'm sure."

"No need, " i assured her. "It's only half a bottle anyway. And we aren't

using it. Why, I dove at least twenty feet deep yesterday when we were

snorkeling and my ears are fine. So you can have it. Let me know your room

number when we get back and I'll put it in your mailbox." There's a little

lattice mailbox outside each stateroom door.

Angela expressed gratitude and Jason shook my hand; and the deal was sealed.

When we arrived back at the ship I put the ear drops in their mailbox as

promised, then retired to my cabin to nap until Michael returned from his tour

of Xunantunich. That seemed to take no time at all; I was awakened from a very

deep sleep by the sound of the stateroom door opening. I opened my eyes to see

Zachary, with Michael coming in behind him

"Guess what, Papa," Zachary said. "Mama fell off the ferry and went to the hospital."

"What?!" I exclaimed. "You're kidding!" I don't know why people say

that, as though anyone (especially a seven-year-old) would make up a joke about such a thing.

But Michael was quick to validate. "No," he said. "Mary fell off a ferry and

broke her shoulder. She's in the infirmary now. She never actually got to see

Xunantunich at all."

It was now time to go up to dinner anyway; and dinner was almost over before

I and the rest of our party had gotten a clear picture of what had happened.

Mary had arrived with the others at the Mayan site, taken one look at the hill

she'd have to climb to get there, and sat under an awning to rest up for the

effort. Suddenly she realized that her little travel pouch was empty.

It had contained her passport, Social Security card, and most importantly her

Sail and Sign card that serves as admittance to the ship and shipboard credit

card. She ran back to the parking lot, took the shuttle back to a small ferry

that crosses a stream, and rode the ferry to the other side where the tourist

buses were parked. Her memory at this point was unclear, but apparently she had

stepped off the ferry before it actually reached shore, losing her balance and

smashing herself against the concrete dock. The ferrymen kept marveling that she

"just jumped off". Mary's depth perception isn't the best; she thinks she may

have misjudged the distance to the shore. In any case, she'd broken her left

humerus, and bruised her face and left eye. The bus driver, who had indeed found

the contents of her travel pouch, insisted on taking her to a private Belize

City hospital emergency room. And off they went.

Meanwhile, Michael and Karen and Zachary had no idea that Mary was injured or

even missing. They thought she was just resting. So, confident she was enjoying

Xunantunich in her own way, they proceeded to explore the site, where the most

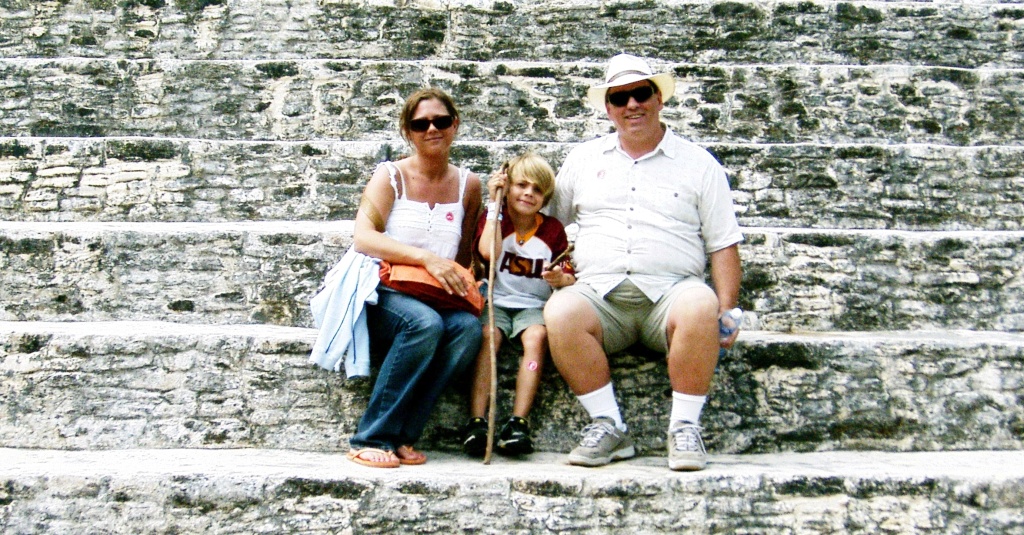

imposing edifice is a pyramid now called El Castillo.

Although it isn't clear from the above picture, there was a banner of

large-scale Mayan hieroglyphs wrapped around the entire building, sort of a

Mayan version of New York's old Times Building on Times Square, with its

stock ticker and news headlines. The Mayans, obviously, didn't have moving

messages but it was impressive, nevertheless, as can be seen in the below photo

of the side of the pyramid, where the hieroglyphs have been restored:

While walking around this pyramid, Zachary got a faraway look in his face and

said, "Most of the city is still underground here." Karen and Michael agreed

that it might be. But a few minutes later, the guide, who had not overheard

Zach, informed the group that most of the city of Xunantunich still awaited

excavation and did, indeed, lie hidden beneath their feet.

Note how high the steps are. Clearly, they weren't meant for everyday

climbing. Nevertheless, tourists today all try to climb them.

Those who succeed, are rewarded by a view of the entire site. To the right

are unexcavated pyramids, much smaller than El Castillo. Obviously this pyramid

commanded the attention and respect of the original inhabitants much as it still

does today.

At lunch time, the tour took a break and the group began to gather for a

lunch of rice and beans in coconut milk, etc.—the same meal I was being served

at the caves. It was at this point that Michael and Karen began to be

concerned when they couldn't find Mary. Karen checked the ladies' room. Michael

looked around all the places people might sit comfortably in the shade; but she

was nowhere to be found. He then went into a gift shop; in leaving,

he began to hear about some woman who'd injured herself on the ferry. Finally,

Karen called down to the buses, to see if she'd gone back there to wait. And

this was when they discovered that Mary was now in a Belizean hospital.

Leaving the lunch uneaten, Michael, Zach and Karen allowed their guide to

take them in a van in search of Mary. The first hospital they went to terrified

Michael. It was a collection of "shacks" connected together, with a barn door

marked "Emergency"..As the personnel searched for any record of Mary's visiting

them, Karen envisioned finding her mother sitting on the floor next to a bunch

of other people with flies walking across their eyeballs. But she could not be

found.

There was another hospital to try, a private one. It was a little nicer than the first, and that's

where they found her. The doctor in charge of Mary's case wanted to keep her

there, but Michael was adamant that Mary not be left in Belize. Mary was equally

insistent, so she was released and another driver from the excursion company

took the foursome to the tenders, which they boarded to return to the ship. Mary

was immediately escorted to the ship's infirmary where the ship's doctor tried

to urge Mary to return to Belize to see a specialist. This doctor was not

the soul of calm and patience. She freaked out because Mary had been sent to the

ship with X-rays but nothing else, including no record of anything they might

already have done.

But, again, Mary insisted on staying aboard the ship. The doctor gave Mary a

mild sedative—which Mary thought

the doctor needed worse than she did—and allowed her to go back to her room. By

special permission, Karen was allowed to bring Mary dinner from Truffles.

After dinner, we left Truffles to visit Mary and make sure she was okay. On

the way, I passed Jason and Angela, who thanked me for the Swimmer's Ear

Solution. "It's already helping," Angela said. "My ear feels a little better.

We'll get it back to you." And she got my room number.

Mary was not in pain, just discomfort. Her bone break was a fracture; she was

bruised but not cut. We were confident that she and Michael had made the right

decision in not staying in Belize—Lord, the logistics nightmare that

would have been! As it was, either Carnival or the excursion company—someone

other than us—had covered the hospital bill.

But with Mary resting in her room, and nothing further than could be done for

her, Michael and I went back to the karaoke lounge near our room. We almost

didn't go, as we were both tired out—for different reasons—and my ear was

feeling a little funny. But we both felt we needed the break. Michael did a

lovely rendition of "Somewhere" from West Side Story (the Streisand

arrangement; Michael's tenor had no problem handling the notes). But after I

sang "You Were Always On My Mind", Sonya the Karaoke Lady asked me to play Elvis

in the end-of-cruise extravaganza. I've never been a big Elvis fan and don't

really know his music. But when Sonya had the audience choose between me and

another guy, I got overwhelming applause and I've always been a sucker for that

sort of thing. So I agreed.

Sonya gave me an MP3 player she said was pre-loaded with two versions of the

Elvis medley I would be singing: One with a vocal, and a music-only karaoke

version to practice with. It was a medley of "Jailhouse Rock" and "You Ain't

Nothin' But A Hound Dog". I had to sign a paper agreeing to do the show and

declaring personal (and financial) responsibility for the MP3 player. But, what

the heck—like Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland, we were going to put on a show!

—Complete with costumes, dancers, and a full-blown orchestra; and how often does

a chance like that come along?

Nothin' But A Hound Dog". I had to sign a paper agreeing to do the show and

declaring personal (and financial) responsibility for the MP3 player. But, what

the heck—like Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland, we were going to put on a show!

—Complete with costumes, dancers, and a full-blown orchestra; and how often does

a chance like that come along?

Michael and I returned to our room more than ready for bed. We got a kick out of tonight's

towel animal—Michael was sure it was a monkey, though to me it looked more like

a Hindu dancer. I checked our mailbox, but the Swimmer's Ear Solution hadn't

made it back. I was sorry, because by now my left ear was throbbing. I realized

that, when I dove while snorkeling with Zach in Cozumel, I had probably picked

up an ear infection. How long has it been since I dove underwater any distance?

Probably ten years. My body was no longer used to this; and even when it was, it

wasn't unusual for me to get ear infections, which was why I had the Swimmer's

Ear Solution to begin with. Like Angela, I had no idea where I was going to find

another bottle of it. Yet, I didn't want to ask for it back. She said

she'd return it; and it would probably be in the mailbox in the morning. I could

wait that long.